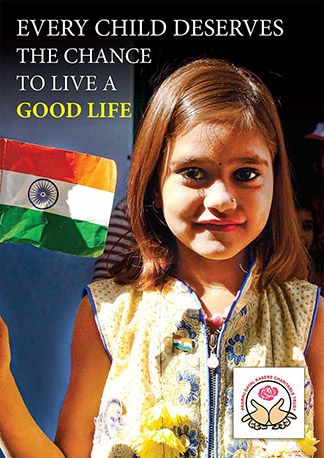

The plight of girls’ education in Afghanistan remains dire as the Taliban continues to enforce severe restrictions on female students beyond third grade, marking a significant setback in gender equality and educational access. Since their return to power in August 2021, the Taliban has implemented a series of bans affecting various aspects of women’s and girls’ lives, including education.

The restrictions are deeply rooted in the Taliban’s interpretation of Islamic law, which has led to a ban on girls attending secondary schools and universities. This policy has excluded nearly half of the population from pursuing education beyond primary school. The international community and several human rights organizations, including the United Nations, have voiced severe concerns over these measures, emphasizing their detrimental impact not just on individual lives but also on the broader socio-economic fabric of Afghanistan.

The Education Ministry has explicitly stated that schools will currently be open only up to grade six for girls, and madrassas (Islamic schools) remain the only form of education available for girls of all ages. However, the curriculum in these religious schools does not support secular educational goals, such as pursuing a career in medicine or engineering, which requires more comprehensive schooling.

The situation has sparked international outcry and repeated calls for the Taliban to lift these educational bans. Catherine Russell, the executive director of UNICEF, described the situation as “absolutely crushing” for Afghan girls, who lose not only their right to education but also future opportunities to contribute significantly to sectors like healthcare and education within their country.

Despite the ongoing international pressure and dialogue, the Taliban’s stance remains unchanged, and the educational future for Afghan girls looks increasingly uncertain. The hardline regime justifies these bans as necessary due to a lack of a “safe environment” for girls, though these assertions are widely criticized by international observers and Afghan citizens alike.

This educational crisis not only halts the progress made over the past two decades during which literacy rates among Afghan women nearly doubled, but it also poses a long-term threat to the country’s development and stability by sidelining half of its potential workforce and intellectual capital.

The article is part of our special news feature on —Human Stories from Forgotten Wars