Japan, the once dominant global technology power and market for high-performance electronics is returning back to the semiconductor business, investing heavily to rebuild its domestic technology capabilities and high-tech industry.

As the global trade gradually grows more volatile due to conflicts, tariffs and disruptions, there is a realisation in Japan, that even though it still boasts some of the most cutting-edge chip fabrication technology in the world, since the 1980s, the country has effectively allowed nations like South Korea and China to take over large-scale production of basic chips betting on globalisation and free trade.

The change in understanding was first triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to large scale disruption of supply chains and a sudden shortage of chips in Europe and the US, making the Japanese government realise that if they were to prevent their domestic industry from going into decline, then they would need their own dedicated supplies of chips. Most recently, Japanese government’s sense of urgency has been heightened by unconventional trade policies introduced by U.S. President Donald Trump, which impede free trade.

Japan not aiming for the top?

“The biggest single factor for the government is ensuring economic security,” Damian Thong, head of Japan equity research and a semiconductor sector specialist at the Macquarie Group in Tokyo has said. Adding, “The feeling is that it is critical that Japan is able to maintain an independent capability in semiconductors in order to meet the needs of its own manufacturers.”

The AI boom of the last couple of years has further focused the Japanese government’s attention on the sector. Despite these pressures, however, Thong believes it is unlikely that Japan is attempting to regain its former position as the world’s dominant chipmaker.

“The government here is not trying to deploy on a global scale,” Thong said in an interview with DW, the german state broadcaster. “It wants to maintain its own scale for Japan but, at the same time, remain relevant and attractive to other foreign companies to come here and set up their own fabrication facilities in the future.”

Taiwan’s semiconductor giant teams up with Sony, Denso

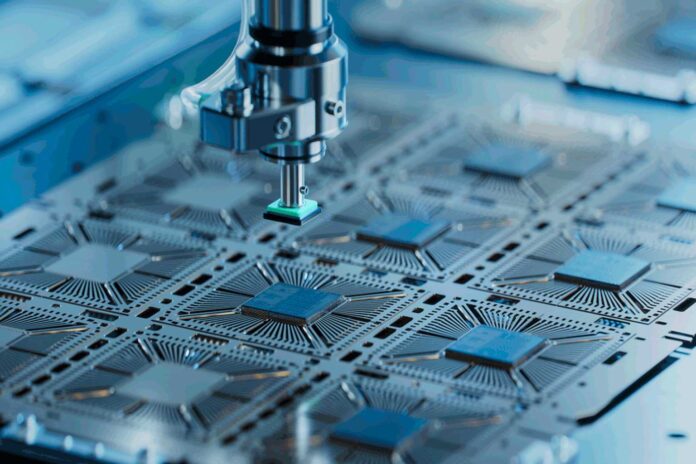

With those goals in mind, Japan has been pursuing a two-pronged strategy to boost domestic production. Firstly, it invited global chip giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) in 2021 to link up with Sony and auto components manufacturer Denso and build a plant in Kumamoto, southern Japan. The project is worth 1.2 trillion yen ($8.01 billion, €7.34 billion) with over 40% financed by government subsidies.

The plant is producing the 22-nanometer and 28-nanometer chips that are used in cars and consumer electronics. In 2023, TSMC announced that it would be building a second fabrication plant in the area due to growing demand.

The second element of the strategy was to create a new Japanese semiconductor manufacturer Rapidus. Since 2022, Japanese government agencies have been funnelling hundreds of millions of dollars into the new company to help it set up production facilities in Hokkaido.

Rapidus is working with the US firm IBM and the Belgian Interuniversity Microelectronics Center (IMEC) organisation to put cutting-edge semiconductor research into production. The government has recently announced that an additional 100 billion yen is being made available to Rapidus under the 2025 budget.

“The objective is to build state-of-the-art chips with other companies to ensure that Japan remains a global player,” said Kazuto Suzuki, a professor of science and technology policy at Tokyo University.

“There is rapidly growing competition in the semiconductor sector, particularly due to the huge demand in the areas of artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, automated driving, drones and others,” he said.

‘Last chance to revitalise’

While Taiwanese manufacturers are now dominating the global market of advanced semiconductors, Japanese companies still excel in producing machinery required to make sophisticated chips. This technology, however, could at some point be acquired by China. Beijing’s increasingly threatening stance on Taiwan, which it views as a breakaway province, is also fuelling concerns of supply disruptions.

Suzuki says Japan has no option but to “step up” to the challenge because the competition “is only going to get tougher.” He also believes that the government is on the right track to ensuring self-sufficiency in chip production.

“Our advantages are that we have the materials required and the equipment necessary to build better semiconductors,” according to the Tokyo-based professor.

“The government sees this as the last chance to revitalise the domestic industry, while we still have the engineers and scientists with the required knowledge,” Suzuki said.

(the article is taken from auto generated news feed)